04.01.2023

Fr Hermann Geissler FSO

Rome

Benedict XVI.

An obituary

With the Te Deum, which the whole Church sings on the last day of the year, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI ended his life here on earth on 31 December 2022. It is difficult to briefly summarise the long life and work of this spiritual giant. But there is something like a "red thread" in his life. It is the service to the faith of the Church, the service of a simple and humble worker in the vineyard of the Lord, as he called himself on the day of his election as Pope on 19 April 2005.

(1) Childhood, youth and education until ordination to the priesthood (1927-1951)

Joseph Ratzinger was born on 16 April 1927 in Marktl am Inn. He was the youngest of three children given to the couple Joseph and Maria Ratzinger. His older sister Maria was born in 1921, his older brother Georg in 1924. Joseph was baptised only four hours after his birth. 16 April was Holy Saturday in that year. Because the celebration of the Resurrection was still celebrated on the morning of Holy Saturday, he was the first to be baptised with the newly consecrated Easter water. "That my life was thus immersed from the beginning ... that my life was so immersed in the Paschal Mystery from the beginning," he wrote himself, "has always filled me with gratitude, for this could only be a sign of blessing. Of course, it was not Easter Sunday, but Holy Saturday. But the longer I think about it, the more it seems to me to be in keeping with the nature of our human life, which is still waiting for Easter, which is not yet in full light, but which is nevertheless trustingly heading towards it" (Aus meinem Leben, 8).

Birthplace of Pope Benedict XVI., Marktl am Inn

Birthplace of Pope Benedict XVI., Marktl am Inn

Joseph grew up in the bosom of a devout family. His father was a gendarme, a man of law. "My father," he testified, "was a very just man, but also a very strict man. But we always felt that he was strict out of kindness. And that is why we could really accept his severity" (Salz der Erde, 49). His mother, who came from South Tyrol, took care of the house and the family and complemented the father with her mildness: "The mother always compensated for what was perhaps too strict about him with her warmth and cordiality" (Salz der Erde, 49). The father was repeatedly transferred for professional reasons. Thus the family moved to Tittmoning in 1929, to Aschau am Inn in 1932 and to Hufschlag near Traunstein in 1937. The Catholic faith was an integral part of life: "Prayers were said at all meals. If it was somehow possible due to the school rhythm, we ... went to mass every day and on Sundays. we went to mass every day and on Sunday we went to church together. Later, when my father was retired, the rosary was also prayed most of the time; otherwise we trusted the school catechesis" (Salz der Erde, 51).

After his First Communion, Joseph, like his brother George, became an altar boy. At a very young age, he wanted the Schott missal so that he could better understand the liturgy. He writes: "It was a captivating adventure to slowly penetrate the mysterious world of the liturgy that was happening there at the altar in front of us and for us. It became increasingly clear to me that I was encountering a reality that had not been invented by anyone.... This mysterious fabric of text and action had grown over centuries out of the faith of the Church" (Aus meinem Leben, 23).

The dark clouds of National Socialism hovered over Joseph Ratzinger's youth. His father was a gendarme in the service of the state. As a staunch opponent of Hitler, he was glad to retire in 1937 and retire to Hufschlag near Traunstein in a rural area. In Traunstein, all three children attended grammar school. Joseph was a very gifted pupil, showed great interest in Greek and Latin, and soon translated Latin hymns into beautiful German. However, during the war, it was 1943, he had to go to Munich as an air force helper together with the other seminarians from Traunstein. In 1944 he was drafted into the Reich Labour Service. After a short period of imprisonment, he was able to return home in June 1945. Throughout his life he fought for freedom of conscience and against any ideology because he had personally experienced the terror of the Nazi regime.

In diesen Jahren reifte im Herzen von Joseph Ratzinger – wie auch seines Bruders Georg – die Berufung zum Priestertum. So traten sie beide 1946 in das Priesterseminar in Freising ein. Dort und auch im Seminar in München hatten sie hervorragende Professoren, die sie in den Reichtum der katholischen Theologie einführten und das Gespräch mit den großen Fragen der Zeit nicht scheuten. Joseph zeigte große Freude am Studium, lernte aber auch, dass zum Priestertum die Bereitschaft zum Dienst an den Menschen gehört: „Ich konnte ja nicht Theologie studieren, um Professor zu werden, auch wenn dies mein stiller Wunsch war. Aber das Ja zum Priestertum bedeutete für mich, ja zu sagen zur ganzen Aufgabe, auch in ihren einfachsten Formen“ (Salz der Erde, 59).

Joseph Ratzinger as young priest.

Joseph Ratzinger as young priest.

On 29 June 1951, Joseph and his brother Georg Ratzinger were ordained priests by Cardinal Faulhaber in Freising Cathedral. This day remained unforgettable for him. "We were more than forty candidates who, when called ADSUM, said: I am here - on a radiant summer day which remains unforgettable as the high point of life. One should not be superstitious. But when, at the moment when the aged archbishop laid his hands on me, a little bird - perhaps a lark - ascended from the high altar into the cathedral and warbled a little song of joy, it was like an encouragement from above: It is good this way, you are on the right path" (Aus meinem Leben, 71). He chose the words of St. Paul as his first words: "We do not want to be lords over your faith, but servants of your joy" (2 Cor 1:24). The joy of faith and the mission to communicate this joy to others characterised his whole life.

(2) Service as chaplain and professor (1951-1977)

In August 1951 he began his service as chaplain in the parish of "Heilig Blut" in Munich. The well-known Father Blumschein worked there, who - as Joseph Ratzinger later wrote - "not only said to others that a priest must glow, but was really an inwardly glowing person" (Aus meinem Leben, 74). This great priestly role model helped the new priest to tackle his tasks courageously: "I had sixteen religion lessons to give in five different classes.... Every Sunday I had to celebrate at least twice and preach two different sermons; every morning I sat in the confessional from 6 to 7 a.m., on Saturday afternoon for four hours. Every week there were several funerals to be held in the various cemeteries of the city. All the youth work was on my shoulders, and in addition there were the extraordinary duties such as baptisms, weddings, etc." (Aus meinem Leben, 74). Working with children and their families soon became a great joy to him. Of course, he also became aware of how far removed from the faith the thinking world of many children already was and how little religious education still found coverage in the lives of families.

The following year he was called back to the Freising seminary to lecture on the pastoral care of the sacraments and to take the exams for his doctorate. He had already written his dissertation as a prize thesis in just one year, on the subject of the people and the house of God in Augustine's doctrine of the Church. Even then he set the basic course for his theological thinking: "The starting point is first of all the Word. That we believe the Word of God, that we try to really get to know it and understand it and then think along with the great masters of faith. Therefore, my theology has a biblical imprint and an imprint from the Fathers, especially from Augustine" (Salz der Erde, 70). In his dissertation, Ratzinger showed from Augustine that the Church is not built by us, but by God, and that it is also not there for itself, but for God to be known by people. The Church is about the mystery of God.

He passed the viva with flying colours. The young doctor of theology was firmly anchored in the faith of the Church and at the same time open to the challenges of the time. He soon took over the chair of dogmatics in Freising and impressed the students with his gift of making the core of faith understandable. In order to be able to take on a professorship, however, he had to write a habilitation thesis. In conversation with his teacher, Professor Söhngen, he came across the great Franciscan scholar Bonaventura. In doing so, he wanted to answer the question why revelation and faith are not backward-looking and do not bind people to a past time. He says about this: "Bonaventure answered this by strongly emphasising the connection between Christ and the Holy Spirit according to the Gospel of John: 'The historical word of revelation is definitive, but it is inexhaustible and always releases new depths'. In this respect, the Holy Spirit, as the interpreter of Christ, speaks with his Word at all times, showing her that this Word has ever new things to say" (Salz der Erde, 66). In other words, Revelation and the Christian faith never become obsolete. They are always current, they have something to say to every generation.

Joseph Ratzinger was habilitated in 1957. In the years that followed, he took over a series of chairs in various places in rapid succession: in 1958 in Freising, 1959 in Bonn, 1963 in Münster, 1966 in Tübingen and 1969 in Regensburg, where he lectured on dogmatics until 1977. It is not possible to go into detail here about his teaching and publications. The aim of his work was to free the faith from templates and encrustations, to make it newly understandable in its freshness and vitality and to bring it into the conversation of the time. Professor Ratzinger was close to the students. At his lectures, the lecture halls were overcrowded. Soon he began to meet regularly with his doctoral students in a "circle of students". He was also respected among his professorial colleagues and in episcopal circles for his competence and human modesty. So we need not be surprised that Cardinal Frings of Cologne chose the young Professor Ratzinger - he was lecturing in Bonn at the time - as his Council theologian.

During the years of the Council, i.e. from 1962 to 1965, Professor Ratzinger was therefore often in Rome. He once described the atmosphere of that time with the following words: "After Pope John had convened the Council and given it the motto to take a leap forward and to aggiornate the faith, as he put it, to bring it into today, there was a very strong will in the Council Fathers to now really dare to do something new" (Salz der Erde, 78). Cardinal Frings and his theologian Ratzinger shared this spirit of departure. Their influence on various Council texts is now well known, especially in the major documents on Revelation, the Church and mission.

Professor Ratzinger was one of the open-minded theologians at the time, but to whom fidelity to the faith of the Church was never a question. That is why he also recognised very quickly, already during the Council, that alongside the good spirit striving for a genuine renewal of the Church, there was also a "spirit of the Council" at work that was to have devastating consequences: "The Fathers wanted to aggiornate the faith - but precisely by doing so they also wanted to offer it in all its force. Instead, the impression developed more and more that reform consisted of simply throwing off ballast; that we were making things easier for ourselves, so that reform now seemed to consist not in a radicalisation of the faith, but in some kind of dilution of the faith" (Salz der Erde, 80). Thus polarisations quickly emerged: For some, the Council was only the springboard to constantly new reforms; by others, the Council was increasingly called into question. Professor Ratzinger said simply:

As already mentioned, Joseph Ratzinger took over the chair of dogmatics in Tübingen in 1966. There he gave a series of lectures on "Introduction to Christianity" for all faculties of the university in 1967. The book, published in 1968, became a bestseller and probably the best-known work of the theologian Joseph Ratzinger. In the preface, he recalls the old story of "Hans in Luck", who traded a lump of gold that was too heavy for him, one by one, in order to be more comfortable, for a horse, for a cow, for a goose, and for a grindstone, which he then threw into the water without losing much more. "The concerned Christian of today ... is not infrequently forced to ask questions like these: Hasn't our theology in recent years often taken a similar path? Has it not gradually interpreted downwards the claim of faith, which was received all too oppressively, always only so little that nothing important seemed to be lost, and yet always so much that one could venture the next step soon afterwards?... A widespread mood (supports) a trend that indeed leads from gold to the grindstone... This is where the intention of the present book comes in: It wants to help to understand faith anew as an enabling of true humanity in our world today, to interpret it without turning it into talk that only with difficulty conceals a complete spiritual emptiness" (Einführung in das Christentum, Gesammte Schriften, Band 4, 31f.) Here we see Joseph Ratzinger's basic theological concern: he wanted to make the treasure of faith understandable in a new way and to show its significance for people and for society today.

(3) Pastoral Service as Archbishop of Munich and Freising (1977-1982).

In 1969, Professor Ratzinger had followed a call to Regensburg. He actually wanted to stay there. His brother Georg directed the famous choir of the Regensburger Domspatzen. His sister Maria, who had accompanied him on all his stages, managed the household and worked as a secretary. He was for a time Dean of the Faculty of Theology and also Vice-Rector of the University and lived through blessed and fruitful years.

In July 1976, the Archbishop of Munich, Cardinal Döpfner, died suddenly. Joseph Ratzinger wrote about this time: "Soon rumours arose that I was among the candidates to succeed him. I could not take them very seriously, for the limits of my health were as well known as my strangeness to tasks of leadership and administration; I knew myself called to the scholarly life" (Aus meinem Leben, 176).

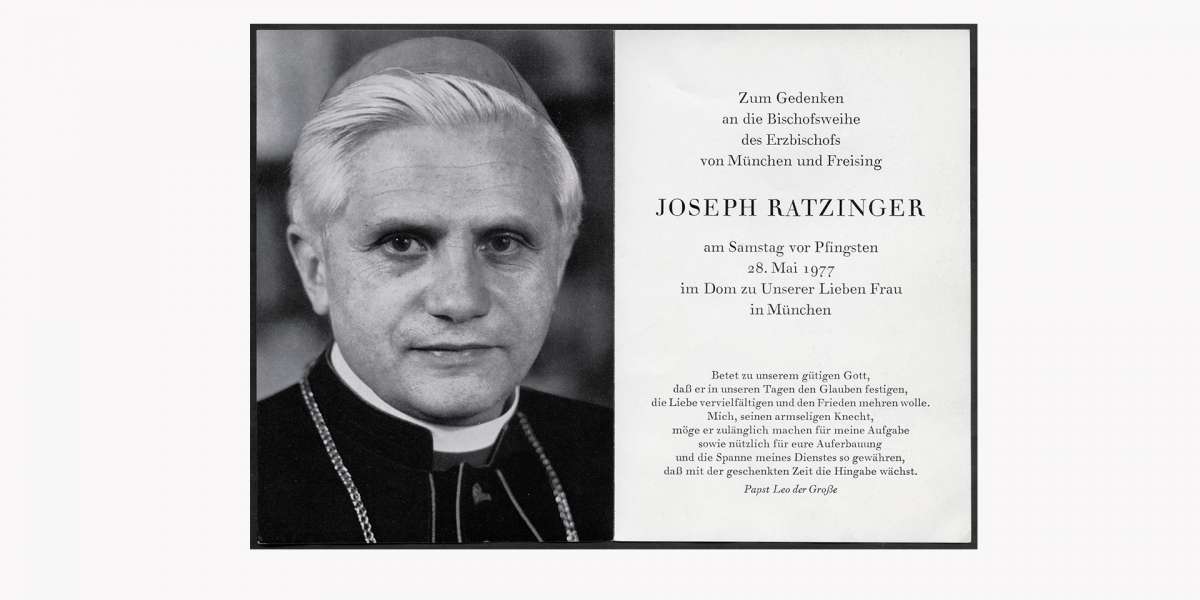

But the following year - Professor Ratzinger was 50 years old - he was indeed appointed Archbishop of Munich and Freising. After a difficult inner struggle, he gave his consent. On the eve of Pentecost 1977, he received the episcopal consecration in Munich's Liebfrauendom: "That day was incredibly beautiful... Munich Cathedral ... was magnificently decorated and filled with an atmosphere of joy that almost irresistibly attacked you. I experienced what sacrament is - that reality happens there. Then the prayer in front of the Marian column in the heart of the Bavarian capital, the encounter with the many people who welcomed the stranger with a cordiality and joy that could not be meant for me at all, but which showed me again what the sacrament is: one welcomed the bishop, the bearer of the mystery of Christ" (Aus meinem Leben, 178).

Episcopal Consecration, Joseph Ratzinger, München und Freising, 28 Mai 1977 (© flickr, CC, Hans-Michael Tappen)

Episcopal Consecration, Joseph Ratzinger, München und Freising, 28 Mai 1977 (© flickr, CC, Hans-Michael Tappen)

He chose a word from the third letter of John as his episcopal motto: "Co-workers of the truth". In this word he saw something like a link between his previous task as a theology professor and his new mission as a bishop: "Despite all the differences, it was and still is about the same thing, to pursue the truth, to be at its service. And because in today's world the subject of truth has almost completely disappeared, because it appears to be too great for man and yet everything falls apart if there is no truth, that is why this motto seemed to me to be timely in a good sense" (Aus meinem Leben, 178f.). He wanted to tackle this great mission together with others. He always sought cooperation so that "the Church may be rightly directed in this hour and the heritage of the Council may be rightly appropriated" (Salz der Erde, 87).

The new archbishop was created a cardinal by Pope Paul VI just a few weeks after his episcopal consecration. He quickly made a name for himself as an eloquent herald of the faith, a fearless critic of grievances and a courageous shepherd who did not avoid conflict. He wrote about his self-image in this time, in which the deficits of the church were clearly before his eyes: "Fatigue of faith, decline of vocations, sinking of moral standards especially among the people of the church, increasing tendency to violence and many other things. The words of the Bible as well as of the Fathers of the Church always ring in my ears, condemning with great severity those shepherds who are like dumb dogs and, in order to avoid conflict, let the poison spread. Quietness is not the first civic duty, and a bishop who would only care about having no trouble and whitewashing all conflicts as much as possible is a chilling vision for me" (Salz der Erde, 88). His priority was always to be a witness of the risen Lord and to strengthen and encourage people in the right faith. Witnessing to the truth and beauty of faith without fear - that was always a matter close to his heart.

(4) Work as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

Soon after his election as Pope in 1978, John Paul II wanted Cardinal Ratzinger to come to Rome, initially as Prefect of the Congregation for Education. But Cardinal Ratzinger asked not to leave Munich immediately, as he had just begun to implement some necessary reforms. In 1981, the Pope again approached Cardinal Ratzinger, this time asking him to take over as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Now he could no longer refuse, and the Pope immediately granted him his wish to continue publishing theological works even as prefect. In March 1982, he began his work at the Congregation, which has the task of promoting and protecting Catholic teaching throughout the world. This is no easy task in our time with all its tremendous challenges and changes. Cardinal Ratzinger knew that as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith he would always have to take criticism. When asked what helped him to keep the peace, he said: "I am a free Christian man and once have to give an account for that before God, not before the media". Cardinal Ratzinger often referred to great witnesses of conscience, such as Thomas More or John Henry Newman, who were role models for him in his mission.

Dikastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (© Wikipedia)

Dikastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (© Wikipedia)

At the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Cardinal Ratzinger promoted a collegial way of working from the very beginning. Decisions on questions that arose were taken together - in the meeting with the staff every Friday. More important questions were always submitted to the Monday meeting of the consultors: The consultors are specialist theologians who work for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. All major decisions were deliberated and decided together by the members of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which includes cardinals and bishops from all over the world, at their monthly Wednesday meeting, and finally submitted to the Pope for approval. This way of working - teamwork in the best sense - was exemplary. Cardinal Ratzinger was once asked why he often wanted to hear the opinion of young collaborators. His answer was: "Already St Benedict says in his Rule that the Holy Spirit can also speak through the youngest". He was an open and listening person throughout his life.

In addition, Cardinal Ratzinger strengthened cooperation with the Bishops' Conferences, especially with the Faith Commissions. From 1984 onwards, he travelled to another continent about every third year to meet the chairpersons of the Faith Commissions there and to discuss pending questions and problems with them. It was of great concern to him to strengthen the responsibility of the bishops and the bishops' conferences for the Catholic faith. He emphasised that in order to pass on the faith in our time, everyone must pull together. The more united the Church is, the more people will experience the power of faith.

Concerned about some theologians who deviate from Church teaching, Cardinal Ratzinger placed a strong emphasis on dialogue and the power of arguments. He repeatedly recalled the ecclesiastical vocation of theologians and had the doctrinal objection procedure thoroughly revised. On the one hand, the rights of individual theologians were to be protected, but on the other hand, the right of the faithful to sound doctrine was to be upheld. In the confrontation with individual theologians, a dialogue lasting years was usually conducted, during which many problems could be solved. Only in very few cases were disciplinary measures necessary.

Cardinal Ratzinger rendered special services to the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The idea for this project was born in 1985 at a synod 20 years after the conclusion of the Council. John Paul II then commissioned a committee headed by Cardinal Ratzinger to prepare the text. An editorial committee assisted the commission. A first draft was submitted to all the bishops' conferences, theological faculties and catechetical institutes. Thousands of suggestions were incorporated into the text, so that one can truly say: This Catechism is a document for the whole Church, and at the same time it was drawn up with the collaboration of the whole Church. In 1992 the Catechism was approved by John Paul II and presented as a "sure and authentic reference text for the exposition of Catholic doctrine". This Catechism will go down in the history of the Church as a document of lasting significance.

In his 23 years at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Cardinal Ratzinger had to deal with a wealth of challenges. At the beginning of the 1980s, liberation theology was a big issue in South America: faith not only wants to show the way to heaven, but also to help improve people's lives here on earth and overcome unjust structures. How far can the church go here? Can it support Marxist currents to stand up for the poor in the struggle against the rich? In two important instructions, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith rejected a Marxist-inspired liberation theology, but then also showed how a genuine gospel-inspired liberation theology works: It starts with liberation from sin, wants to contribute to the renewal of hearts and thus also promotes justice in politics and economics.

Another major problem was and is relativism, which claims that objective truth does not exist at all, but only subjective opinions, that all religions are paths to salvation, that Christ is only one of many founders of religions. To correct such currents, which also reach into the Church, the declaration Dominus Iesus was published in 2000. In it, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith says that only one is Lord and Saviour: Jesus Christ, who died and rose for all people. Followers of other religions can be saved if they sincerely follow their conscience, but not through Buddha, Mohammed or anyone else, but through Jesus Christ, the only mediator between God and man. The various religions are, as it were, man's search for the mystery of God, but Christ is God's answer to this search of man. Therefore, the Church must also proclaim the Gospel to all people today.

There were also new questions in the area of bioethics. Let us think of artificial insemination, embryo research and much more. Under Cardinal Ratzinger, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith made it clear that the Church advocates unconditional respect for the embryo from conception and that new human life, according to the Creator's plan, should be the fruit of conjugal love. Against gender ideology, the Congregation reminded us that man and woman have equal dignity, but are willed differently by the Creator and are meant to complement each other precisely in their difference for the good of all.

Throughout these years, it was clear that Cardinal Ratzinger was not only a close collaborator, but also a personal friend and advisor of John Paul II. There is no doubt that great encyclicals of this Pope, such as Veritatis splendor on fundamental questions of morality, Evangelium vitae on the protection of life, or Fides et ratio on faith and reason, also bear his signature. Cardinal Ratzinger was a pillar of the faith, a brilliant theologian and a humble servant on whom John Paul II could fully rely.

(5) Pontificate of Benedict XVI. (2005-2013) and his life as Pope emeritus (2013-2022)

When John Paul II died in 2005, Cardinal Ratzinger was Dean of the College of Cardinals. Therefore, he had to preside over the funeral. His words about the late Pope standing at the window of heaven, looking down on us and blessing us, touched many people deeply. Cardinal Ratzinger was also responsible for presiding over the conclave, and he himself was then elected Pope - already on the 2nd day of the conclave - on 19 April 2005.

Pope Benedict XVI. 2010 (© flickr, CC, Catholic Church England and Wales)

Pope Benedict XVI. 2010 (© flickr, CC, Catholic Church England and Wales)

Benedict XVI knew that as a 78-year-old he could not tackle any special projects in the leadership of the Church. "I was aware," he said in retrospect, "that above all I had to try to show what faith means in today's world, to re-emphasise the centrality of faith in God and to give people courage to believe" (Last Conversations, 28). With what programme did the new Pope set about this task? In his homily at the inauguration he said that his programme was "not to do my will, not to impose my ideas, but to listen together with the whole Church to the word and will of the Lord and to let myself be led by him, so that he himself may lead the Church in this hour of our history" (Homily, 24 April 2005). Here we hear the heartbeat of Benedict XVI.

We must content ourselves with a few brief references to how, listening to the Lord, he sought to encourage people in the faith. He gave us three encyclicals on the divine virtues of faith, hope and charity. Deus caritas est (2005): "God is love" is the title of his first encyclical. In it, he presented us anew with the mystery of God incarnate and our basic mandate to love God and our neighbour. In his second encyclical Spe salvi (2007), he underlined the topicality of Christian hope in a world that often tends towards resignation and fear of the future. And the encyclical Lumen fidei (2013), prepared by him but then published by Pope Francis, shows us how faith is light on our path and how it is passed on - like a burning torch - from person to person. In the social encyclical Caritas in veritate (2009), he addressed all people of good will and underlined the importance of the integral development of man in love and in truth. "The humanism that excludes God is an inhuman humanism" (No. 78), we read in this letter.

Benedict XVI called several synods of bishops. The themes dealt with at these all had to do with faith: the first Synod was about the celebration of faith in the liturgy (Sacramentum caritatis, 2006), the second was about the Word of God that nourishes our faith (Verbum Domini, 2010), the third was about the new evangelisation and the transmission of faith in our secularised world (2012).

During the Wednesday catecheses, Benedict XVI very often focused on the saints, starting with the Apostles, the Fathers of the Church, the saintly figures of the Middle Ages up to the holy women and men of modern times. They are the great shining lights of the faith, the real renewers of the Church and the world.

Many of the speeches, reflections and homilies that Benedict XVI gave us are unforgettable. Many faithful, listening to his words, had the experience of the Emmaus disciples who, after the disappearance of the strange guest, said to each other: "Did not our hearts burn in our breasts when he spoke to us on the way and opened to us the meaning of the Scriptures?" (Lk 24:32).

Benedict XVI gave clear orientation in the dispute over the interpretation of Vatican Council II: for the right understanding of the texts, a "hermeneutics of reform while preserving continuity" is needed (Address to the Roman Curia, 22 December 2005). The Council did not want a break with the past. It did not want a different Church, but a renewed Church - a Church that recalls its sustaining roots and is able to bring Christ to the modern world.

Throughout his life, the Pope Emeritus saw the inner centre of the Church in the sacred liturgy, in which the primacy of God is expressed. He worked with the Council for the genuine renewal of the liturgy, but also wanted to help overcome the break with tradition. The re-admission of the traditional liturgy through the letter Summorum pontificum (2007) therefore not only accommodated traditionally-minded Catholics, it was also understood as a contribution to the reconciliation of the Church with its own past.

On his travels, Benedict XVI brought the Good News to many countries. He himself counted the trips to the World Youth Days among the most beautiful of his entire pontificate: "Cologne, Sydney, Madrid, these are three incisions in my life that I will never forget" (Last Conversations, 225). His main concern was to encourage young people in the joy of faith. German speakers probably particularly remember his trips to his Bavarian homeland, to Mariazell and Vienna, as well as to Berlin, Erfurt and Freiburg, where his address on "de-worldliness" triggered a process that Pope Francis is now continuing.

We cannot go into detail here about the progress in ecumenism, especially with the Orthodox Churches, the good relations with Judaism and the other religions, and the many meetings with politicians and statesmen. In any case, Benedict always endeavoured to reach out to all people, to appeal to their conscience, to promote the good in them. He did not avoid crises in the Church and in Rome, but tackled them as best he could. And in addition to all his duties as Pope, he managed to write a three-volume book about Jesus of Nazareth. This work was particularly close to his heart because "the Church is at an end... when we no longer know Jesus" (Last Conversations, 235).

Some people criticised Benedict XVI, saying that he had been more professor than pastor. He himself responded to this criticism: "I tried to be a shepherd above all. Of course, this also includes passionately dealing with the Word of God, which is what a professor is supposed to do. In addition, there is being a confessor. The terms professor and confessor mean roughly the same thing philologically, although the task is naturally more in the direction of confessor" (Letzte Gespräche, 266). Benedict was a Confessor Pope, a connoisseur and confessor of the faith.

And then came that 11 February 2013 that had the whole world on tenterhooks. Benedict XVI announced his resignation. He did so because he was a sober-minded man and realised that he no longer had the strength to exercise the office of Pope in our difficult times. Added to this was his faithful certainty that the Lord would continue to care for his Church and give her a new Pope. And finally, he was a great example of humility: only a humble person can take such a step.

At his last unforgettable audience on 27 February 2013, he said of his resignation:

For the past almost ten years, the Pope Emeritus has carried out this ministry of prayer for the Church and especially for his successor Pope Francis.

During his last meeting with the faithful, Benedict XVI called out to the faithful in St Peter's Square: "I have always known that the Lord is in the boat of the Church and ... that the boat of the Church does not belong to me, not to us, but to Him.... I want to invite everyone to renew their firm trust in the Lord.... I want everyone to feel loved by that God who gave his Son for us and showed us his boundless love. I want everyone to feel the joy of being a Christian.... Yes, let us be joyful in the gift of faith; it is the most precious thing that no one can take away from us!"

In his spiritual testament, written on 29 August 2006 and published by the Holy See on 31 December 2022, he calls us:

In this faith Joseph Ratzinger lived, for this faith he worked, in this faith he died. He deserves heartfelt thanks for his extraordinary service to the faith, for his clarity, his courage and his humility. Only after he goes home to the heavenly Father will the world realise what a great gift this Confessor Pope is and remains for humanity.